Difference between revisions of "1989 AIME Problems/Problem 15"

(→Solution 5(Mass of a point+ Stewart+heron)) |

(→Solution: added solution) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

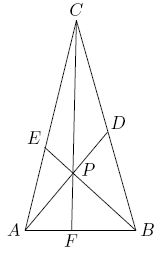

[[Image:AIME_1989_Problem_15.png|center]] | [[Image:AIME_1989_Problem_15.png|center]] | ||

| − | == Solution == | + | == Solutions == |

| − | === Solution | + | |

| + | == Solution 1 == | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let <math>[RST]</math> be the area of polygon <math>RST</math>. We'll make use of the following fact: if <math>P</math> is a point in the interior of triangle <math>XYZ</math>, and line <math>XP</math> intersects line <math>YZ</math> at point <math>L</math>, then <math>\dfrac{XP}{PL} = \frac{[XPY] + [ZPX]}{[YPZ]}.</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <center><asy> | ||

| + | size(170); | ||

| + | pair X = (1,2), Y = (0,0), Z = (3,0); | ||

| + | real x = 0.4, y = 0.2, z = 1-x-y; | ||

| + | pair P = x*X + y*Y + z*Z; | ||

| + | pair L = y/(y+z)*Y + z/(y+z)*Z; | ||

| + | draw(X--Y--Z--cycle); | ||

| + | draw(X--P); | ||

| + | draw(P--L, dotted); | ||

| + | draw(Y--P--Z); | ||

| + | label("$X$", X, N); | ||

| + | label("$Y$", Y, S); | ||

| + | label("$Z$", Z, S); | ||

| + | label("$P$", P, NE); | ||

| + | label("$L$", L, S);</asy></center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is true because triangles <math>XPY</math> and <math>YPL</math> have their areas in ratio <math>XP:PL</math> (as they share a common height from <math>Y</math>), and the same is true of triangles <math>ZPY</math> and <math>LPZ</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We'll also use the related fact that <math>\dfrac{[XPY]}{[ZPX]} = \dfrac{YL}{LZ}</math>. This is slightly more well known, as it is used in the standard proof of [[Ceva's theorem]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now we'll apply these results to the problem at hand. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <center><asy> | ||

| + | size(170); | ||

| + | pair C = (1, 3), A = (0,0), B = (1.7,0); | ||

| + | real a = 0.5, b= 0.25, c = 0.25; | ||

| + | pair P = a*A + b*B + c*C; | ||

| + | pair D = b/(b+c)*B + c/(b+c)*C; | ||

| + | pair EE = c/(c+a)*C + a/(c+a)*A; | ||

| + | pair F = a/(a+b)*A + b/(a+b)*B; | ||

| + | draw(A--B--C--cycle); | ||

| + | draw(A--P); | ||

| + | draw(B--P--C); | ||

| + | draw(P--D, dotted); | ||

| + | draw(EE--P--F, dotted); | ||

| + | label("$A$", A, S); | ||

| + | label("$B$", B, S); | ||

| + | label("$C$", C, N); | ||

| + | label("$D$", D, NE); | ||

| + | label("$E$", EE, NW); | ||

| + | label("$F$", F, S); | ||

| + | label("$P$", P, E); | ||

| + | </asy></center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since <math>AP = PD = 6</math>, this means that <math>[APB] + [APC] = [BPC]</math>; thus <math>\triangle BPC</math> has half the area of <math>\triangle ABC</math>. And since <math>PE = 3 = \dfrac{1}{3}BP</math>, we can conclude that <math>\triangle APC</math> has one third of the combined areas of triangle <math>BPC</math> and <math>APB</math>, and thus <math>\dfrac{1}{4}</math> of the area of <math>\triangle ABC</math>. This means that <math>\triangle APB</math> is left with <math>\dfrac{1}{4}</math> of the area of triangle <math>ABC</math>: | ||

| + | <cmath> [BPC]: [APC]: [APB] = 2:1:1.</cmath> | ||

| + | Since <math>[APC] = [APB]</math>, and since <math>\dfrac{[APC]}{[APB]} = \dfrac{CD}{DB}</math>, this means that <math>D</math> is the midpoint of <math>BC</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Furthermore, we know that <math>\dfrac{CP}{PF} = \dfrac{[APC] + [BPC]}{[APB]} = 3</math>, so <math>CP = \dfrac{3}{4} \cdot CF = 15</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We now apply [[Stewart's theorem]] to segment <math>PD</math> in <math>\triangle BPC</math>—or rather, the simplified version for a median. This tells us that | ||

| + | <cmath> 2 BD^2 + 2 PD^2 = BP^2+ CP^2. </cmath> Plugging in we know, we learn that | ||

| + | <cmath> \begin{align*} | ||

| + | 2 BD^2 + 2 \cdot 36 &= 81 + 225 = 306, \\ | ||

| + | BD^2 &= 117. \end{align*} </cmath> | ||

| + | Happily, <math>BP^2 + PD^2 = 81 + 36</math> is also equal to 117. Therefore <math>\triangle BPD</math> is a right triangle with a right angle at <math>B</math>; its area is thus <math>\dfrac{1}{2} \cdot 9 \cdot 6 = 27</math>. As <math>PD</math> is a median of <math>\triangle BPC</math>, the area of <math>BPC</math> is twice this, or 54. And we already know that <math>\triangle BPC</math> has half the area of <math>\triangle ABC</math>, which must therefore be 108. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Solution 2 === | ||

Because we're given three concurrent [[cevian]]s and their lengths, it seems very tempting to apply [[Mass points]]. We immediately see that <math>w_E = 3</math>, <math>w_B = 1</math>, and <math>w_A = w_D = 2</math>. Now, we recall that the masses on the three sides of the triangle must be balanced out, so <math>w_C = 1</math> and <math>w_F = 3</math>. Thus, <math>CP = 15</math> and <math>PF = 5</math>. | Because we're given three concurrent [[cevian]]s and their lengths, it seems very tempting to apply [[Mass points]]. We immediately see that <math>w_E = 3</math>, <math>w_B = 1</math>, and <math>w_A = w_D = 2</math>. Now, we recall that the masses on the three sides of the triangle must be balanced out, so <math>w_C = 1</math> and <math>w_F = 3</math>. Thus, <math>CP = 15</math> and <math>PF = 5</math>. | ||

Recalling that <math>w_C = w_B = 1</math>, we see that <math>DC = DB</math> and <math>DP</math> is a [[median]] to <math>BC</math> in <math>\triangle BCP</math>. Applying [[Stewart's Theorem]], <math>BC^2 + 12^2 = 2(15^2 + 9^2)</math>, and <math>BC = 6\sqrt {13}</math>. Now notice that <math>2[BCP] = [ABC]</math>, because both triangles share the same base and the <math>h_{\triangle ABC} = 2h_{\triangle BCP}</math>. Applying [[Heron's formula]] on triangle <math>BCP</math> with sides <math>15</math>, <math>9</math>, and <math>6\sqrt{13}</math>, <math>[BCP] = 54</math> and <math>[ABC] = \boxed{108}</math>. | Recalling that <math>w_C = w_B = 1</math>, we see that <math>DC = DB</math> and <math>DP</math> is a [[median]] to <math>BC</math> in <math>\triangle BCP</math>. Applying [[Stewart's Theorem]], <math>BC^2 + 12^2 = 2(15^2 + 9^2)</math>, and <math>BC = 6\sqrt {13}</math>. Now notice that <math>2[BCP] = [ABC]</math>, because both triangles share the same base and the <math>h_{\triangle ABC} = 2h_{\triangle BCP}</math>. Applying [[Heron's formula]] on triangle <math>BCP</math> with sides <math>15</math>, <math>9</math>, and <math>6\sqrt{13}</math>, <math>[BCP] = 54</math> and <math>[ABC] = \boxed{108}</math>. | ||

| − | === Solution | + | === Solution 3 === |

Using a different form of [[Ceva's Theorem]], we have <math>\frac {y}{x + y} + \frac {6}{6 + 6} + \frac {3}{3 + 9} = 1\Longleftrightarrow\frac {y}{x + y} = \frac {1}{4}</math> | Using a different form of [[Ceva's Theorem]], we have <math>\frac {y}{x + y} + \frac {6}{6 + 6} + \frac {3}{3 + 9} = 1\Longleftrightarrow\frac {y}{x + y} = \frac {1}{4}</math> | ||

| Line 24: | Line 86: | ||

Using area ratio, <math>\triangle ABC = \triangle ADB\times 2 = \left(\triangle ADQ\times \frac32\right)\times 2 = 36\cdot 3 = \boxed{108}</math>. | Using area ratio, <math>\triangle ABC = \triangle ADB\times 2 = \left(\triangle ADQ\times \frac32\right)\times 2 = 36\cdot 3 = \boxed{108}</math>. | ||

| − | === Solution | + | === Solution 4 === |

Because the length of cevian <math>BE</math> is unknown, we can examine what happens when we extend it or decrease its length and see that it simply changes the angles between the cevians. Wouldn't it be great if it the length of <math>BE</math> was such that <math>\angle APC = 90^\circ</math>? Let's first assume it's a right angle and hope that everything works out. | Because the length of cevian <math>BE</math> is unknown, we can examine what happens when we extend it or decrease its length and see that it simply changes the angles between the cevians. Wouldn't it be great if it the length of <math>BE</math> was such that <math>\angle APC = 90^\circ</math>? Let's first assume it's a right angle and hope that everything works out. | ||

| Line 42: | Line 104: | ||

[however, I think this solution is wrong, the A, B, and Cs do not match with the picture] | [however, I think this solution is wrong, the A, B, and Cs do not match with the picture] | ||

| − | === Solution | + | === Solution 5 === |

First, let <math>[AEP]=a, [AFP]=b,</math> and <math>[ECP]=c.</math> Thus, we can easily find that <math>\frac{[AEP]}{[BPD]}=\frac{3}{9}=\frac{1}{3} \Leftrightarrow [BPD]=3[AEP]=3a.</math> Now, <math>\frac{[ABP]}{[BPD]}=\frac{6}{6}=1\Leftrightarrow [ABP]=3a.</math> In the same manner, we find that <math>[CPD]=a+c.</math> Now, we can find that <math>\frac{[BPC]}{[PEC]}=\frac{9}{3}=3 \Leftrightarrow \frac{(3a)+(a+c)}{c}=3 \Leftrightarrow c=2a.</math> We can now use this to find that <math>\frac{[APC]}{[AFP]}=\frac{[BPC]}{[BFP]}=\frac{PC}{FP} \Leftrightarrow \frac{3a}{b}=\frac{6a}{3a-b} \Leftrightarrow a=b.</math> Plugging this value in, we find that <math>\frac{FC}{FP}=3 \Leftrightarrow PC=15, FP=5.</math> Now, since <math>\frac{[AEP]}{[PEC]}=\frac{a}{2a}=\frac{1}{2},</math> we can find that <math>2AE=EC.</math> Setting <math>AC=b,</math> we can apply Stewart's Theorem on triangle <math>APC</math> to find that <math>(15)(15)(\frac{b}{3})+(6)(6)(\frac{2b}{3})=(\frac{2b}{3})(\frac{b}{3})(b)+(b)(3)(3).</math> Solving, we find that <math>b=\sqrt{405} \Leftrightarrow AE=\frac{b}{3}=\sqrt{45}.</math> But, <math>3^2+6^2=45,</math> meaning that <math>\angle{APE}=90 \Leftrightarrow [APE]=\frac{(6)(3)}{2}=9=a.</math> Since <math>[ABC]=a+a+2a+2a+3a+3a=12a=(12)(9)=108,</math> we conclude that the answer is <math>\boxed{108}</math>. | First, let <math>[AEP]=a, [AFP]=b,</math> and <math>[ECP]=c.</math> Thus, we can easily find that <math>\frac{[AEP]}{[BPD]}=\frac{3}{9}=\frac{1}{3} \Leftrightarrow [BPD]=3[AEP]=3a.</math> Now, <math>\frac{[ABP]}{[BPD]}=\frac{6}{6}=1\Leftrightarrow [ABP]=3a.</math> In the same manner, we find that <math>[CPD]=a+c.</math> Now, we can find that <math>\frac{[BPC]}{[PEC]}=\frac{9}{3}=3 \Leftrightarrow \frac{(3a)+(a+c)}{c}=3 \Leftrightarrow c=2a.</math> We can now use this to find that <math>\frac{[APC]}{[AFP]}=\frac{[BPC]}{[BFP]}=\frac{PC}{FP} \Leftrightarrow \frac{3a}{b}=\frac{6a}{3a-b} \Leftrightarrow a=b.</math> Plugging this value in, we find that <math>\frac{FC}{FP}=3 \Leftrightarrow PC=15, FP=5.</math> Now, since <math>\frac{[AEP]}{[PEC]}=\frac{a}{2a}=\frac{1}{2},</math> we can find that <math>2AE=EC.</math> Setting <math>AC=b,</math> we can apply Stewart's Theorem on triangle <math>APC</math> to find that <math>(15)(15)(\frac{b}{3})+(6)(6)(\frac{2b}{3})=(\frac{2b}{3})(\frac{b}{3})(b)+(b)(3)(3).</math> Solving, we find that <math>b=\sqrt{405} \Leftrightarrow AE=\frac{b}{3}=\sqrt{45}.</math> But, <math>3^2+6^2=45,</math> meaning that <math>\angle{APE}=90 \Leftrightarrow [APE]=\frac{(6)(3)}{2}=9=a.</math> Since <math>[ABC]=a+a+2a+2a+3a+3a=12a=(12)(9)=108,</math> we conclude that the answer is <math>\boxed{108}</math>. | ||

Revision as of 02:20, 10 April 2022

Contents

Problem

Point ![]() is inside

is inside ![]() . Line segments

. Line segments ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are drawn with

are drawn with ![]() on

on ![]() ,

, ![]() on

on ![]() , and

, and ![]() on

on ![]() (see the figure below). Given that

(see the figure below). Given that ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , find the area of

, find the area of ![]() .

.

Solutions

Solution 1

Let ![]() be the area of polygon

be the area of polygon ![]() . We'll make use of the following fact: if

. We'll make use of the following fact: if ![]() is a point in the interior of triangle

is a point in the interior of triangle ![]() , and line

, and line ![]() intersects line

intersects line ![]() at point

at point ![]() , then

, then ![]()

![[asy] size(170); pair X = (1,2), Y = (0,0), Z = (3,0); real x = 0.4, y = 0.2, z = 1-x-y; pair P = x*X + y*Y + z*Z; pair L = y/(y+z)*Y + z/(y+z)*Z; draw(X--Y--Z--cycle); draw(X--P); draw(P--L, dotted); draw(Y--P--Z); label("$X$", X, N); label("$Y$", Y, S); label("$Z$", Z, S); label("$P$", P, NE); label("$L$", L, S);[/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/3/c/9/3c978a1fdb0a6c3a79b9ee477956a440b734f13b.png)

This is true because triangles ![]() and

and ![]() have their areas in ratio

have their areas in ratio ![]() (as they share a common height from

(as they share a common height from ![]() ), and the same is true of triangles

), and the same is true of triangles ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

We'll also use the related fact that ![]() . This is slightly more well known, as it is used in the standard proof of Ceva's theorem.

. This is slightly more well known, as it is used in the standard proof of Ceva's theorem.

Now we'll apply these results to the problem at hand.

![[asy] size(170); pair C = (1, 3), A = (0,0), B = (1.7,0); real a = 0.5, b= 0.25, c = 0.25; pair P = a*A + b*B + c*C; pair D = b/(b+c)*B + c/(b+c)*C; pair EE = c/(c+a)*C + a/(c+a)*A; pair F = a/(a+b)*A + b/(a+b)*B; draw(A--B--C--cycle); draw(A--P); draw(B--P--C); draw(P--D, dotted); draw(EE--P--F, dotted); label("$A$", A, S); label("$B$", B, S); label("$C$", C, N); label("$D$", D, NE); label("$E$", EE, NW); label("$F$", F, S); label("$P$", P, E); [/asy]](http://latex.artofproblemsolving.com/7/c/9/7c9e14d181ecf013675ff1bfbe1aee4cc51d0c7e.png)

Since ![]() , this means that

, this means that ![]() ; thus

; thus ![]() has half the area of

has half the area of ![]() . And since

. And since ![]() , we can conclude that

, we can conclude that ![]() has one third of the combined areas of triangle

has one third of the combined areas of triangle ![]() and

and ![]() , and thus

, and thus ![]() of the area of

of the area of ![]() . This means that

. This means that ![]() is left with

is left with ![]() of the area of triangle

of the area of triangle ![]() :

:

![]() Since

Since ![]() , and since

, and since ![]() , this means that

, this means that ![]() is the midpoint of

is the midpoint of ![]() .

.

Furthermore, we know that ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

We now apply Stewart's theorem to segment ![]() in

in ![]() —or rather, the simplified version for a median. This tells us that

—or rather, the simplified version for a median. This tells us that

![]() Plugging in we know, we learn that

Plugging in we know, we learn that

![]() Happily,

Happily, ![]() is also equal to 117. Therefore

is also equal to 117. Therefore ![]() is a right triangle with a right angle at

is a right triangle with a right angle at ![]() ; its area is thus

; its area is thus ![]() . As

. As ![]() is a median of

is a median of ![]() , the area of

, the area of ![]() is twice this, or 54. And we already know that

is twice this, or 54. And we already know that ![]() has half the area of

has half the area of ![]() , which must therefore be 108.

, which must therefore be 108.

Solution 2

Because we're given three concurrent cevians and their lengths, it seems very tempting to apply Mass points. We immediately see that ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Now, we recall that the masses on the three sides of the triangle must be balanced out, so

. Now, we recall that the masses on the three sides of the triangle must be balanced out, so ![]() and

and ![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Recalling that ![]() , we see that

, we see that ![]() and

and ![]() is a median to

is a median to ![]() in

in ![]() . Applying Stewart's Theorem,

. Applying Stewart's Theorem, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Now notice that

. Now notice that ![]() , because both triangles share the same base and the

, because both triangles share the same base and the ![]() . Applying Heron's formula on triangle

. Applying Heron's formula on triangle ![]() with sides

with sides ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Solution 3

Using a different form of Ceva's Theorem, we have ![]()

Solving ![]() and

and ![]() , we obtain

, we obtain ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Let ![]() be the point on

be the point on ![]() such that

such that ![]() .

Since

.

Since ![]() and

and ![]() ,

, ![]() . (Stewart's Theorem)

. (Stewart's Theorem)

Also, since ![]() and

and ![]() , we see that

, we see that ![]() ,

, ![]() , etc. (Stewart's Theorem)

Similarly, we have

, etc. (Stewart's Theorem)

Similarly, we have ![]() (

(![]() ) and thus

) and thus ![]() .

.

![]() is a

is a ![]() right triangle, so

right triangle, so ![]() (

(![]() ) is

) is ![]() .

Therefore, the area of

.

Therefore, the area of ![]() .

Using area ratio,

.

Using area ratio, ![]() .

.

Solution 4

Because the length of cevian ![]() is unknown, we can examine what happens when we extend it or decrease its length and see that it simply changes the angles between the cevians. Wouldn't it be great if it the length of

is unknown, we can examine what happens when we extend it or decrease its length and see that it simply changes the angles between the cevians. Wouldn't it be great if it the length of ![]() was such that

was such that ![]() ? Let's first assume it's a right angle and hope that everything works out.

? Let's first assume it's a right angle and hope that everything works out.

Extend ![]() to

to ![]() so that

so that ![]() . The result is that

. The result is that ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() because

because ![]() . Now we see that if we are able to show that

. Now we see that if we are able to show that ![]() , that is

, that is ![]() , then our right angle assumption will be true.

, then our right angle assumption will be true.

Apply the Pythagorean Theorem on ![]() to get

to get ![]() , so

, so ![]() and

and ![]() . Now, we apply the Law of Cosines on triangles

. Now, we apply the Law of Cosines on triangles ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Let ![]() . Notice that

. Notice that ![]() and

and ![]() , so we get two nice equations.

, so we get two nice equations.

![]()

![]()

Solving, ![]() (yay!).

(yay!).

Now, the area is easy to find. ![]() .

.

[however, I think this solution is wrong, the A, B, and Cs do not match with the picture]

Solution 5

First, let ![]() and

and ![]() Thus, we can easily find that

Thus, we can easily find that ![]() Now,

Now, ![]() In the same manner, we find that

In the same manner, we find that ![]() Now, we can find that

Now, we can find that ![]() We can now use this to find that

We can now use this to find that ![]() Plugging this value in, we find that

Plugging this value in, we find that ![]() Now, since

Now, since ![]() we can find that

we can find that ![]() Setting

Setting ![]() we can apply Stewart's Theorem on triangle

we can apply Stewart's Theorem on triangle ![]() to find that

to find that ![]() Solving, we find that

Solving, we find that ![]() But,

But, ![]() meaning that

meaning that ![]() Since

Since ![]() we conclude that the answer is

we conclude that the answer is ![]() .

.

Solution 5(Mass of a point+ Stewart+heron)

Firstly, since they all meet at one single point, denoting the mass of them separately. Assuming ![]() ; we can get that

; we can get that ![]() ; which leads to the ratio between segments,

; which leads to the ratio between segments,

![]() . Denoting that

. Denoting that ![]()

Now we know three cevians' length, Applying Stewart theorem to them, getting three different equations:

After solving the system of equation, we get that ![]() ;

;

pulling ![]() back to get the length of

back to get the length of ![]() ; now we can apply Heron's formula here, which is

; now we can apply Heron's formula here, which is

Our answer is ![]() ~bluesoul

~bluesoul

See also

| 1989 AIME (Problems • Answer Key • Resources) | ||

| Preceded by Problem 14 |

Followed by Final Question | |

| 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 • 10 • 11 • 12 • 13 • 14 • 15 | ||

| All AIME Problems and Solutions | ||

These problems are copyrighted © by the Mathematical Association of America, as part of the American Mathematics Competitions. ![]()